It’s long been debated whether videogames count as a legitimate form of art or not. Early on the size and average age of any given game’s audience and the limitations of the hardware it ran on made gaming easy to dismiss as just a line of toys. But today things are a bit different. Gamers have grown up and the games have grown with them. Major new releases eclipse movie premiers. Production budgets number in the tens of millions, and many high-profile actors lend their voices and motion captures to videogame performances. Yet for all its success, the gaming industry still hasn’t been able to definitively end the videogames-are-art debate. Some developers have tried by going ‘cinematic’ and reducing the amount of player involvement in a game and painting everything in a gray color pallette so you know it’s dead serious. But while this approach may take after art in a way, these kinds of mainstream titles are not really what prove gaming’s worth as an art form. By and large Hollywood has devolved into regurgitating the same clichéd content over and over, each revolution providing steadily less and less substance, thus the games that try to imitate Hollywood for its professionalism may set the benchmark for what modern gaming hardware can do, but rarely do they result in the sort of creative work that will be remembered for decades down the road. So if mere cinematic composition can’t prove the artfulness of videogames, what can? Well, plenty. It’s true of any art form that what sells the most isn’t necessarily the best or most artistic the medium has to offer, and likewise it’s mostly beneath the surface of mainstream gaming that the real gems are found. In its highest form gaming is primarily a storytelling medium, not a competition (though that’s not to say competitive genres are illegitimate videogames), and when used as a storytelling medium correctly it can provide the kind of experience art mediums of the past only ever dreamed of. That’s right, not only are videogames a viable art form, but when used as art they’re the ultimate art form ever devised by humanity. A bold statement? Perhaps, and yet…not so much.

All art forms rolled into one

At one point in time, at least the arguments against videogames made some sense. Today, though, they just plain don’t hold water. To dismiss games as an art form is to dismiss all other art forms, because games are all art forms rolled into one—the culmination of millennia of discovering, creating, and exploring new mediums. Over the years textures have grown to steadily higher and higher resolutions to the point where now each one is an intricate example of traditional artistry given digital form. Characters sometimes numbering in the dozens are each designed with care. Stories and scripts glue them all together, usually accompanied by voice acting or even just plain acting via motion capture. And the soundtracks—oh, the soundtracks! Gaming is home to some of the most talented composers alive. And all that is to say nothing of the code that makes the final product a reality.

All videogames may not be art, but all art has a place in videogames. They’re a sort of meta-art, and should be judged both as a whole and on the account of each art sub-category. Some older games don’t have brilliant graphics, but find their strength in story and music (e.g. Final Fantasy). Some modern games don’t have much substance in the way of narrative, but feature breathtaking vistas just begging to be explored and appreciated (e.g. Crysis). And now that they’ve been around long enough, some even have no obvious weaknesses at all and absolutely nail it in every possible category (e.g. Valkyria Chronicles).

You are the main character

But gaming isn’t merely the ultimate art form in its delivery. It’s also a critical step forward in how it is experienced. Sure, books and movies have long been in the business of putting people in the shoes of fictional characters, but always at a distance. Even first-person stories have to tell the reader what to see and how to react to it. Videogames do not. Instead they craft the atmosphere and circumstances and leave the rest up to the player. Will you be intimidated? Courageous? Heartbroken? Indifferent? How your emotions are engaged will affect your experience with a game. Even if the path the story follows is perfectly linear and doesn’t change based on your actions, it’s still up to you to successfully complete each segment. That’s not just watching moving pictures on a screen. That’s being the main character’s eyes, ears, hands, and feet. And the power of that level of connectedness between story and player should not be underestimated. As the main character develops relationships with other characters, those relationships start to feel personal and real. In-game experiences can leave actual marks on real people’s lives. There’s a degree of personal investment that other art forms just can’t manage alone.

For the long haul

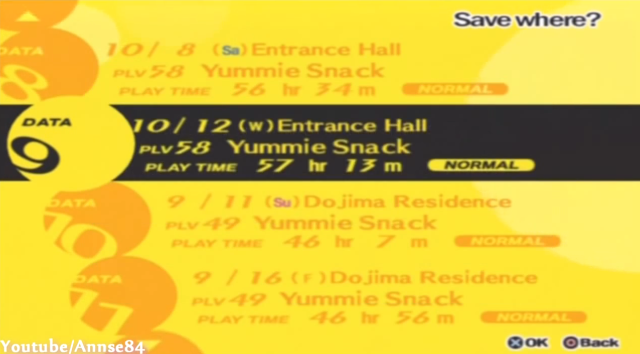

How long is the average movie? A couple of hours. TV shows fare a bit better at 12 or 13 hours a season. In this regard, videogames are more like books. Length varies highly from game to game, and may largely depend on each player’s style and/or ability, but as time has gone on the standard length of videogames has grown to the point where anything less than 10 hours is considered paltry. Many break the 30-hour mark, others twice that and beyond. Talk about personal investment.

With those kinds of figures, actually finishing a game can be something genuinely special, like parting ways with a best friend and returning to your normal lives after spending a few weeks or months saving the world together. If that doesn’t affect you in any way, you might want to check your pulse.

Work for it

But let’s not forget that these are still games we’re talking about, here. There’s still strategy, puzzles, and challenges galore. While some might see this as precisely the factor preventing games from being art, in practice it actually adds to the experience by making the player work to carry forward the story at hand. By artificially inducing real difficulty to a fictional plot games overcome a weakness present in most other forms of media: the ever-present knowledge that everything will somehow work itself out. In a videogame there is always a win/loss scenario, at minimum. Some will allow characters to permanently die if not protected or rescued by the player, or put an element of choice into the story which can branch the plot off into radically different paths depending on the player’s decisions. Not only do the actual game elements of a videogame strongly contribute to the idea of ‘personal investment’, but they oftentimes showcase the creativity of the developers in how they build those game elements into the story they wish to craft and vice versa. And again, games require code—not what is usually thought of as an art form, but perhaps it should be, considering its close relationship with art.

Of the same stuff

And not videogame art only. We live in a digital age where anything that calls itself art is distributed as code of one kind or another. If images, movies, music, and books are no less art when transferred to digital form, why should they be thought less of as videogames? Either way, they’re made of the same stuff—a thing that, like paint, is not art in and of itself, but a vehicle for it.

In the end, gaming doesn’t need to find its validation as an art form in imitation of other art forms or even in their approval. It’s already a higher form of art on its own when in the right hands—a meta-art willing and able to showcase the best all forms of art collectively have to offer, and an interactive art capable of most deeply affecting its consumers.

Are videogames art? It’s harder to imagine how they wouldn’t be.