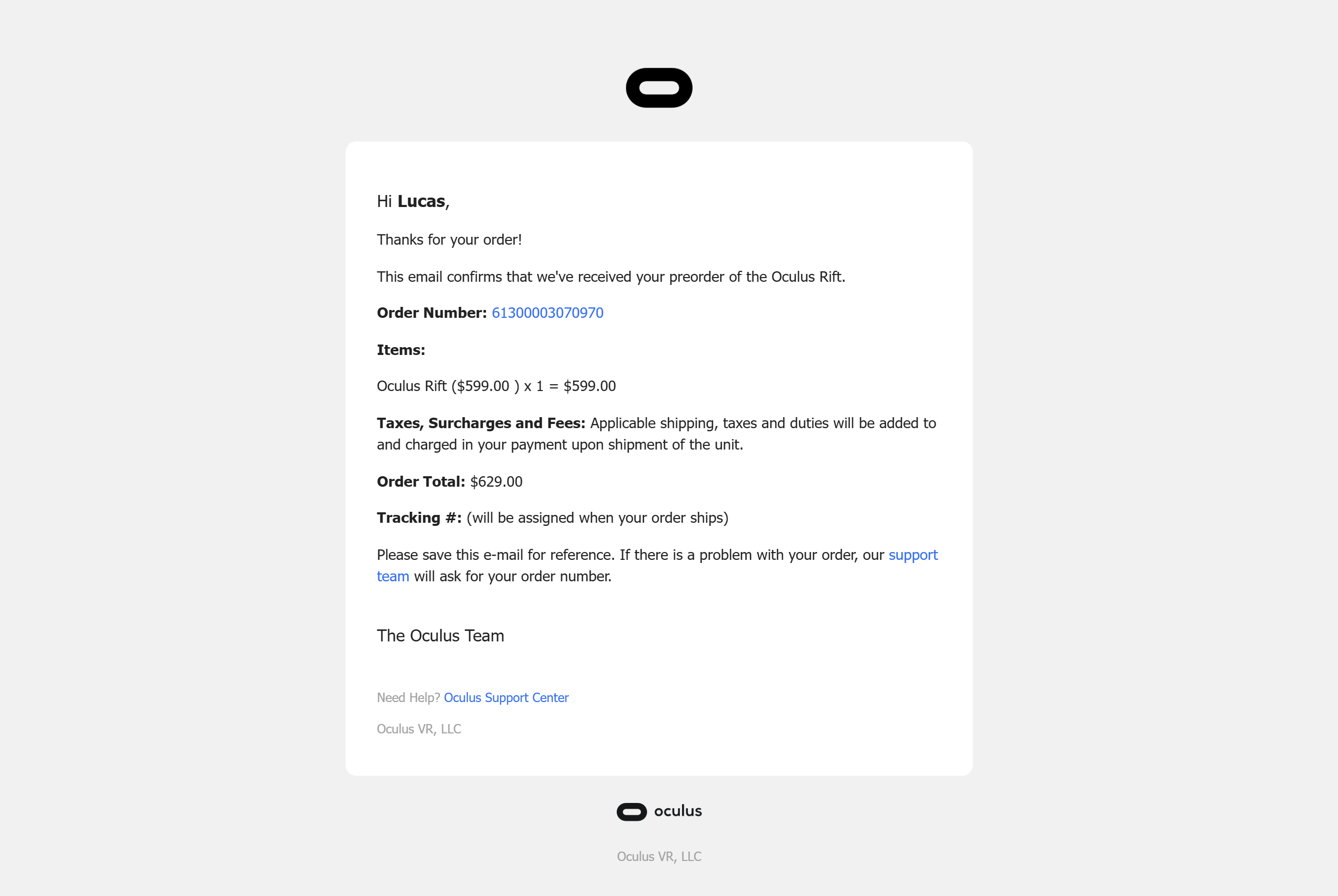

I still remember where I was the night preorders went live for the Oculus Rift on January 6th, 2016. I'd spent the whole day following news and community posts whenever there was a spare moment at work. I'd watched the preorder numbers go up with anxiety, fearing if I waited too long, I'd end up weeks behind the first shipments.

The $600 price tag revealed at the time was quite the sticker shock, given the then-steep PC requirements to go along with it. But as I sat in my chair, contemplating my decision, I knew there was only one answer.

This wasn't, after all, just another tech purchase. This was a chance to be among the first humans ever to step into a whole new digital world—a new reality. Few products ever carry such a huge promise. This was the stuff of dreams! Literally, in a sense, albeit less fleeting and with full awareness and control.

Compared to that, what's $600 anyway?

And so it was that I placed my preorder, number 61300003070970, and awaited its arrival with feverish anticipation.

It didn't take long for community members to dissect the order numbering scheme and identify whose orders were in which batches, then build spreadsheets to predict when each one would ship. We religiously consumed any new YouTube video of someone lucky enough to get an early hands-on demo, or better yet, their own unit. (You can see my own unboxing video here.)

As with anything that doesn't exist yet, the possibilities were endless. But we also knew going in that there would be compromises at first. Being tethered to a PC, finagling with external tracking sensors for maximum coverage—these things would go away in time. But they were sacrifices any enthusiast was willing to make for access to the VR experience.

Now, 10 years later, the prospect of Virtual Reality remains just as exciting as it ever was. But looking back, it feels a bit like we took a wrong turn somewhere in history and ended up with the opposite future we anticipated.

The cables? The sensors? Pancake lenses? Hand tracking? The hardware advancements we could only dream of in 2016 became a reality far sooner than anyone dared hope. The only problem is, we ultimately traded that VR experience for them. And unlike the temporary compromises of 2016, this problem isn't looking to correct itself anytime soon.

Pinpointing where it all went wrong isn't difficult. Consumer VR was never going to take off as a pricey peripheral for an even more lavish PC. The PC was an anchor as much as an asset. It was powerful, sure. But even disregarding the added cost of entry, reliance on third-party desktop-oriented operating systems added immeasurable friction to the user experience, and business risks besides.

There is no question that standalone VR was (and is!) the way forward. It's also understandable that Meta (then Facebook) prioritized shifting to this paradigm at all costs. But a cost there was: in hardware capabilities, yes, but more significantly, in software culture.

Mobile computer hardware has maintained a pretty consistent pace of advancement 10 years or so behind its desktop counterparts. The Qualcomm Adreno 740 GPU in your Quest 3 from 2022 is roughly equivalent to an NVIDIA GTX 680 from 2012, albeit with more modern rendering features. And yet, a quick glance at games released in the same era will reveal a shocking upgrade in visual quality compared to the VR titles of today.

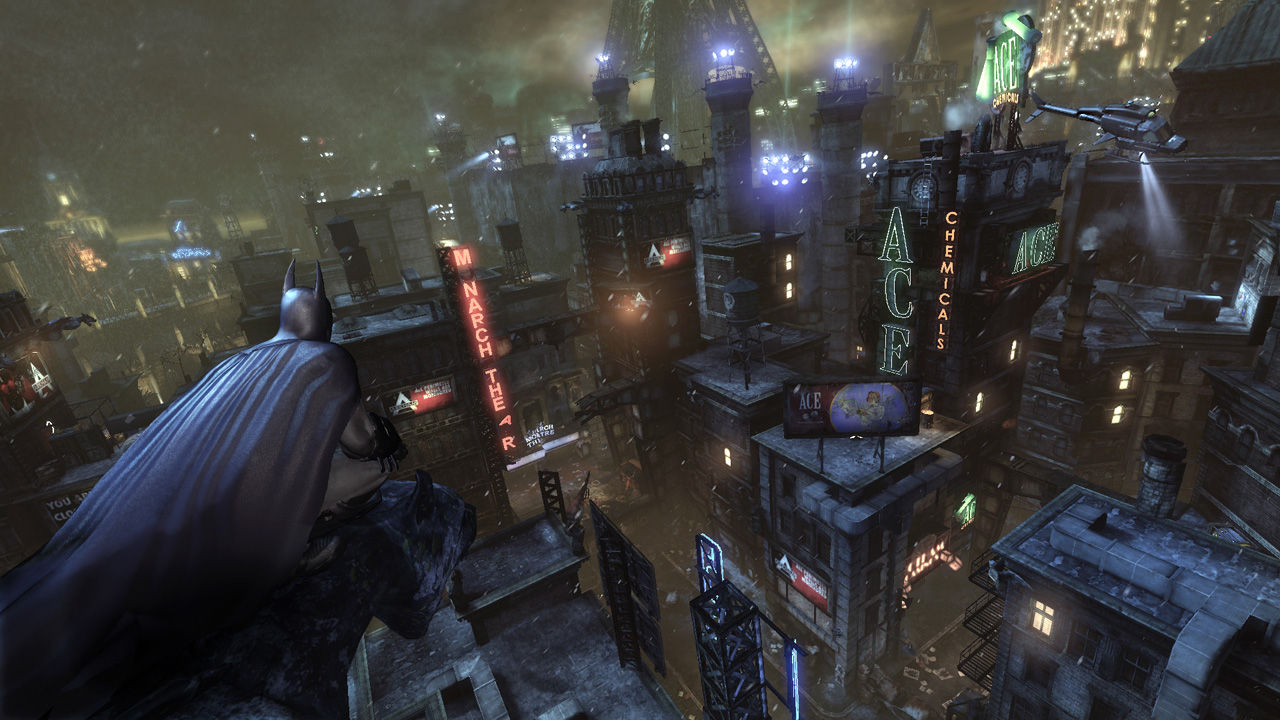

Batman: Arkham City, Crysis 2, Battlefield 3—just to name a few—all games that look great to this day, and all ran excellently on the GTX 680, tracking over 60 FPS even at the kind of high resolutions demanded by VR. And before you argue that games back then didn't need to render two perspectives (one for each eye): yes, in fact, they did. NVIDIA 3D Vision was the ultimate high-end gaming accessory at the time, and GPUs like the 680 were heavily marketed for their stereoscopic rendering capabilities.

So, how is it that, despite today's mobile hardware matching yesterday's beefiest gaming PCs, most VR experiences feel more like they're stuck on Nintendo 64?

Well, it wasn't always this way. Early PC VR titles were largely developed by industry veterans hot off the heels of the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360. While VR posed many new challenges both for optimization and mechanics, the core principles remained the same. Unlike modern games which rely on vast open worlds, level streaming, and simulated systems, these games prioritized small, bespoke levels with relatively simple logic and geometry. Artful textures and clever GPU shaders created the impression of detail that didn't necessarily exist. It didn't have to. Games used to be defined by their creative vision—a cohesive look, sound, and feel, all focused on bringing a singular dream to life.

In VR circles, we had a different word for it: presence.

They may seem like two different concepts at first. "Presence", after all, originally described the feeling when your brain stops thinking about the fact you're wearing a headset and simply accepts the experience as real. But that kind of transcendence was only ever possible in software engineered to create it.

By now, we've all seen the gimmicks of Oculus Dreamdeck, yet it still feels just as awe-inspiring today as it did 10 years ago. Why? The visuals may be a bit dated, but each demo takes itself so seriously that you can't help but treat them with respect. Everything from the menu to the eerie 3D sound effects are dripping with atmosphere. There's an inherent aura of sophistication and scale, making you believe in the endless possibilities of the digital realm.

Or what of EVE: Valkyrie, a space dogfighting spinoff of the EVE Online universe? In any other medium, the long activation sequence for your fighter craft would be a drag, but in VR, it becomes just as gut-wrenching as a real flight preparing for takeoff. You can practically feel the G-forces as you shoot out the launch tube and burst into a vast asteroid field dotted with stars, nebulae, and enemy ships. Every moment and every detail is designed to ground you in the experience, and there's nothing quite like it to this day.

And speaking of space ships, none will ever feel quite so much like home as that of Farlands, a surprise pack-in title by Oculus itself. It's still one of the most convincing VR backdrops I've ever stood in, and while quaint, the game itself isn't half bad either! The whimsical creatures are endearing and just interactive enough to feel alive. But what really stands out are the environments. In today's parlance, Farlands would likely be branded a "cozy game". There's little to push you forward towards your objectives; instead, you're allowed to explore at your leisure, and no matter where you look, near or far, there's something compelling to behold.

And let's not forget The Unspoken. Developed by Insomniac Games—yes, that one—this Oculus Touch launch title dropped players in an ordinary city where extraordinary magic battles take place. Simply put, Insomniac's pedigree is on full display here. Animations are lively and fluid. The arenas are stylized, yet realistic and detailed. Casting spells employs a full range of gestures, each with satisfying feedback and visual effects to connect your physical body to your character's actions. While the onboarding process is a bit lengthy and unforgiving, it's filled to the brim with moments that make you exclaim, "I can do that!?"

I miss games like Dead and Buried, Ripcoil, Robo Recall, Lone Echo, and the rest. Not all aimed for photorealism, but all aimed to push the boundary and immerse you in fully-realized play spaces.

These days, however, that attitude is a rarity. The runaway success of sandbox and social games like VRChat, Gorilla Tag, and Rec Room—not to mention their flatscreen inspirations—have shifted developer priorities away from VR as a gateway to a new reality and more as a 3D web browser instead.

Titles such as these broke the system in every conceivable way. They were visually simplistic, appealed primarily to children, and in most cases, were even free to play. That wasn't at all the Oculus model of mature, premium experiences to subsidize hardware sales. The reality of the ecosystem didn't line up with traditional studios' ambitions. Although Meta initially hesitated to embrace it (owing to the legal risks of marketing VR to minors), eventually they too jumped on the bandwagon with Horizon Worlds, a first-party clone of everything that already came before it.

The result? A platform dominated by indie developers without the experience, resources, and cultural context to really push VR forward. Without the directorial spirit to have a vision to push VR forward. Instead, VR offers two things: a platform with low competition and a low barrier to entry. And because it's still immersive with or without presence, people will keep coming back anyway.

Modern game developers almost universally cut their teeth on general-purpose engines such as Unity or Unreal. While these certainly can push boundaries in the right hands, they can also waste resources with impunity. Less experienced developers are more likely to prioritize user-friendly solutions over efficient ones. Think building a model with Lego versus 3D printing: the result may be functional, but lack finesse or internal consistency.

There's also a problem of design priority. Modern applications are typically built big, then scaled down. This process doesn't take into account the strengths and weaknesses of target hardware, but simply strips things out to fit. There's no fallback to older, cheaper techniques, shifting workloads across specialized chips, or using creative art styles to overcome physical limitations. There's no director budgeting visual elements to keep the soul of the product intact.

In the end, everything winds up looking just... kind of flat.

Some noteworthy exceptions do exist, of course. Batman: Arkham Shadow did an incredible job adapting the series to VR, with visual fidelity not far off from Arkham games of yore running on that NVIDIA GTX 680. The developers of Red Matter 2 famously created their own custom shaders optimized for mobile GPUs. And let's not get started on Half-Life: Alyx.

But then, at the same time, there's games like Assassin's Creed Nexus, or Thief: Legacy of Shadow—respectable efforts that will entertain existing fans, but ultimately feel more like the modern equivalent of handheld spinoffs from the early 2000s. "Portable editions" of games for the Nintendo DS or Sony PSP were sometimes great in their own right, but more often only substitutes for the "real" games you'd rather be playing on other systems.

Of course, we know how history played out there. Eventually, we got the Nintendo Switch. Then, handheld gaming PCs. Mobile technology didn't catch up, per se, but it crossed a critical threshold where it had enough in common with desktop counterparts that it could run the same software, just with a few knobs and dials adjusted.

In my humble opinion, Meta needed Quest 3 to be VR's Switch moment. It wasn't. Instead of really pushing for hardware equivalence with much bigger platforms, Quest 3 was a collection of iterative quality-of-life improvements over Quest 2 before it. Welcome improvements, to be sure, but iterative nonetheless. It's telling that only a short while later, Meta released the Quest 3S offering only the improved performance and a better price tag. Two steps forward, one step back, as they say.

There's a prevailing narrative that consumers don't care about spec sheets—and they don't. Just like they don't care what cameras were used to film their favorite movies, or what PCs the VFX team was using. But everyone innately feels it when a movie looks great, when the soundtrack really hits, and when the story tugs at your heartstrings.

Despite all the naysayers, 10 years later, VR is not dead, nor is it going anywhere anytime soon. But somewhere along the line, we lost track of what really matters that makes VR a worthwhile medium. It's not just another social gold rush for corporate exploitation, it's a whole new world.

A new reality… still waiting to be explored.